Archives: Georgia’s Chaotic Memory

By Irakli Khvadagiani, a research fellow at Soviet Past Research Laboratory (SovLab)

The emergence of modern archival institutions and networks in Georgia is linked to the Russian imperial administration in the 19th century. The Georgian Democratic Republic received this heritage in 1918 and undertook fundamental reforms to preserve the nation’s memory. This is the story of many an unsung hero.

Building Imperial Memory

In the beginning of the 19th century, Russia first annexed the Kingdoms of Kartli-Kakheti (eastern Georgia) and then of Imereti (western Georgia), slowly transforming the entire South Caucasus into the Empire’s outlying province, centered around the Viceroy seated in Tbilisi. The new provincial and regional government has launched into systematization and centralization of the government business, which naturally required long-term record-keeping.

Simultaneously, the local imperial administration launched an ethnographic study of the Caucasus, actively collecting the artifacts and sources. This endeavor was a part of an effort to document its own conquest and cast it in an appropriate academic and political light. These efforts have logically created a need for storing the collected historical and ethnographic materials.

The first official archival institution and a storage were created at the Chancellery of the Viceroy of the Caucasus in the early 1800s. Each imperial institution has opened their own archives. When these official bodies were restructured or abolished, the archive would either move to the new institution, or would be transferred into central archival storage, in Tiflis.

It was in these times, that a number of important and rich archival collections have emerged. Most notable among them were the archives of the Chancelleries of the Governor and of the Viceroy of the Caucasus; the archives of the Caucasus Main General Staff and the Military District Staff; the archives of the Marshal of Nobility of Tiflis Governorship; the archives of the Council of Nobility of Tiflis; the archives of the diplomatic chancellery of the Viceroy of the Caucasus, as well as the archives of the Governorship.

Starting in 1817, Georgia-Imereti Synodal Office, the Russian Empire’s supreme clerical authority in the Caucasus, started to amass old church documents, including deeds and manuscripts. The archive was located in Tiflis and the archivist was appointed in 1824. The records show, that in this establishment in contrast with the imperial archives, the systems of document registration, classification and storage remained in a deplorable condition by the end of the century.

The Archeographic Commission of the Caucasus was founded in 1864 tasked to identify and study the sources reflecting historical, geographic and ethnographic characteristics of the Caucasus as well as to document Russia’s civilian governance in the Caucasus. The commission existed until 1917 publishing 12 volumes of its Collections of Proceeds, an invaluable source of information. The documents and materials collected by the commissions were stored in their own archives.

Civic Memory

By the end of the 19th century, along with the imperial archival structures, civic and scientific organizations operating began to emerge, and started to search and systematize historical vestiges, artifacts and documentary sources. This civic activism has eventually resulted in the emergence of libraries and archival units at these organizations and highlighted the need for specialization.

Founded in 1879, the Society for the Spreading the Literacy among Georgians, along with its core educational mission, had also set as its original objective to preserve the historical, documentary heritage.

For years, the “reading hall/museum” of the organization amassed old deeds and rare print editions. By 1915, the Society had already collected 1956 old manuscripts, 1341 deeds, 4058 Georgian and 5185 foreign language print editions. The Society was scientifically processing, and periodically publishing these sources.

Starting in 1888, the Tiflis Museum of Antiquities began functioning in the city; later it was transformed into the Church Museum.

The Historical-Ethnographic Society of Georgia founded in 1907 made a great contribution to collection and scientific study of historical sources. By the 1920s, the Society had collected 15 239 old historical documents, 4 018 artifacts, 2 705 Georgian and 9 784 foreign language print editions.

During the 1930s, the archives belonging to the all of these societies, as well as some additional historical documents separated from other official archives were handed over to the Department of Manuscripts under the State Museum of Georgian Soviet Socialist Republic that was subsequently transformed into the National Center of Manuscripts, which still functions today.

Private Memories

At the turn of the 20th century, individual citizens – researchers and educators – also made their contribution to identifying historical documents and creating document collections; later, their private libraries and document collections turned into valuable archival and library collections.

The contribution made by Isidore Kvitsaridze, a Kutaisi-based educator, publisher, bibliophile and owner of the bookstore “Imereti”, is of particular importance. A collection of Georgian periodicals, gathered and catalogued by Kvitsaridze became the core of the library collection of the Georgian-language press from the 1920s.

Manuscripts that Burn

Chaos brought about by the World War I, and subsequent disintegration of the Russian Empire had tragic and fundamental impact on historical document collections.

What would become the series of mass destruction of historical sources in Georgia began in 1914.

The Ottoman Empire was on the offensive at the beginning of the World War I. Driving deeply into the southern underbelly of the Russian Empire they have caused panic in the Caucasus Administration.

The Russian Empire started to evacuate administration, taking archives of strategically important state agencies, as well as of the museums to the North Caucasus with them.

Even through the Ottoman advances were quickly checked, and the front-line had soon stabilized, the authorities, busy with wartime effort, were not in a rush to bring the evacuated assets back. The drawn out process return was delayed further as the Empire started to fray – the 1917 revolution, the Bolshevik coup and civil war in Russia have ensued.

Throughout this time, the evacuated archival collections were stored in absolutely inadequate conditions. Many pieces were damaged, destroyed or scattered due to neglect.

Only in 1923, when independent Georgia was already subdued and integrated into Soviet Union, the special expedition of the Main Archival Bureau managed to recuperate what has remained.

Notably, even without the political upheavals, the archives of the local and government offices were far from perfection, in terms of cataloguing and storage conditions. The collapse of the Russian Empire and disintegration of the imperial administration, as well as turbulence and chaos of the First Republic in 1917-1920 led to further scattering and destruction – at times intentional, but more often due to neglect – of a part of archives belonging to local administrative institutions of the Empire.

As the Empire shattered, some civil servants – especially in police and security services – have destroyed the compromising materials. Thus, the archives of the Office of the Gendarmerie of the Kutaisi Governorate and Batumi Police were burnt down in 1917.

The First Republic

As Georgia declared its independence in 1918, the new government undertook to edify new state institutions and ensure public stability in extremely complicated circumstances.

The consequences of the World War I were catastrophic. In its wake, left at the frontier of the two crumbling empires – the Russian and the Ottoman – the First Republic was on a war footing almost constantly, especially in 1918-1919.

As a result, the much required fundamental renewal of the state administration was constantly delayed. Putting the archives of the state administration and the collections of the historical and cultural preservation institutions in order was not a priority.

Unfortunately, there is no fundamental and detailed study to document state policy in the First Democratic Republic of Georgia regarding the archival reform in 1918-1921.

Traces of information appear in the documents dating back to late 1920s, but these are highly biased, written under Bolshevik administration which tried to to discredit the Democratic Republic.

Still, we can glean some basic information to reconstruct the contours of policy.

Amid relative stabilization of foreign and domestic political situation, in 1920 the Democratic Republic started to introduce fundamental legal frameworks and to promote institutional development in all fields of public life.

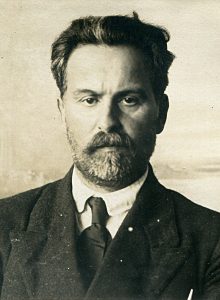

On April 23, 1920, the Constituent Assembly of Georgia adopted a decree on founding the Central Scientific Archive of the Republic of Georgia. Petre Geleishvili, member of the assembly, longtime member of the Social-Democratic Party and known publicist, was appointed as its head.

Geleishvili served as an archivist of the Social-Democratic Party of Georgia which operated underground until 1917; thus, he was intimately familiar with the peculiarities and problems of the archival sphere.

The building of the former District Military Court, which stood on what is Tbilisi’s Kostava Street today, became the home of the Central Scientific Archive.

As far as one can gather, the Central Archive has started to search and identify the archival collections scattered throughout the country, aiming to ensure their protection and centralization. We can glean the degree of disorganization that reigned from the fragments of reports and letters prepared by the Central Scientific Archive:

“… The condition of archives is quite hopeless. During the entire period of our work [March-May 1920], we found only one archive, which is more or less well arranged: this is the archive of territorial department (located at the District Court)… With this exception, the Tiflis archives can be divided into two groups. One group of archives has been uniformly processed… but since in most cases there are not even simple listings of preserved materials, and where these lists are available (in two or three cases), they are incomplete, much preliminary work needs to be done to clarify what each archive contains and under by how they have been categorized.

The second group of archives is completely messy. The files are scattered about on the floor. Once complete file folders lay detached. The archival rooms are full of dust and garbage… As far as we know, in provincial institutions, old files are being sold as scrap paper’s price. According to Deputy Minister of Commerce and Industry, Prof. Avaliani, the archives belonging to the Kutaisi provincial control chamber were sold at Kutaisi market; according to Leo Shengelaia, chairman of the Zugdidi Municipality, he has completely by accident [saved] a valuable archive belonging to the Dadiani family…”

Sovietization

The ongoing process of systematization and coordination of Georgian archives was significantly hampered by Soviet Russia’s occupation of the Republic of Georgia in February-March 1921 that marked the beginning of a qualitatively new and difficult era in the history of the country.

However, it has also marked the beginning of a decisive moment in terms of archival policy, since the present Georgian archival space acquired its broad shape just then, under the Soviet rule.

In February-March 1921, during the ongoing occupation by Soviet troops, the government of the Democratic Republic has evacuated state property and museum treasures, and along with these, a part of the administrative archives.

These archival documents were stored abroad, at the disposal of the exiled government and, later, at the Universities of Harvard and of Paris.

These documents were handed over to the Georgian National Archive in the 2000s; however, the fate of the archives belonging to one, particularly important institution – Special Unit (Security Service) of the Interior Ministry of the Democratic Republic of Georgia – is still unknown.

We know for certain that this archive was moved abroad in 1921 and it was apparently stored in France; however, its trace has been lost, complicating scientific research of this important issue.

This post is also available in: ქართული (Georgian)