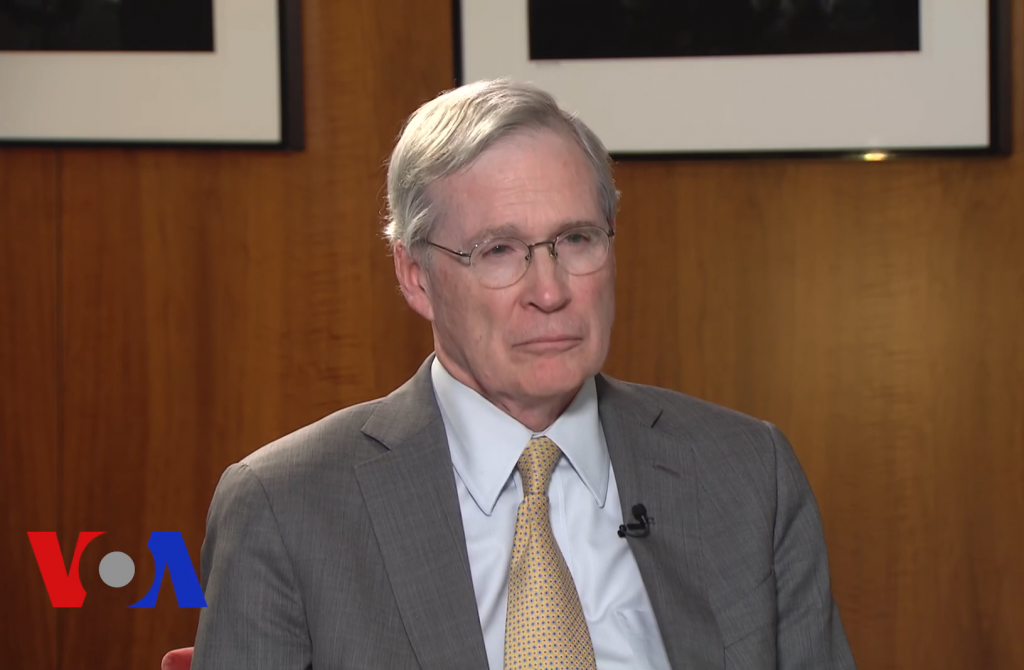

Stephen Hadley was President George W. Bush’s National Security Advisor in 2005-2009. In an exclusive interview with the Voice of America’s Georgian Service, he recalls the events leading up to the Russian invasion of Georgia in 2008 and the steps the Bush Administration took in response to this aggression.

Ia Meurmishvili anchors Voice of America Georgian Service’s weekly show Washington Today and can be followed on Twitter @iameurmishvili or on Facebook /ia.meurmishvili.

This August marks the 10th anniversary of Russian invasion of Georgia. How do you recollect the events leading up to the war? What was discussed in the White House as the signs of the trouble were becoming clearer?

We saw a lot of evidence of preparations and buildup. It was hard to read exactly what the Russian intentions were, but it was certainly worrying and troubling. What President Bush tried to do was both make clear that we supported Georgia – and the President offered his personal support to Saakashvili at that time – but also, counseled him not to provoke Russia, because a military intervention would be something Georgia could not handle. It was not clear that we would be able to deter it or prevent it. So it was a combination of trying to show support for Georgia, for Georgian independence, but at the same time, advising not to provoke Russia and not to provoke Putin. Regrettably, that combination was not sufficient.

In 2005, President Bush visited Georgia.

I was there. It was a great day, a great visit. Very inspiring!

It was a historic visit. President Bush famously called Georgia a Beacon of Democracy. Some people claim that because of this support, Saakashvili thought that he had unconditional support from the United States. What do you think?

I do not remember it that way. I remember Saakashvili’s visit at the White House and his meeting with President Bush at the Oval Office. He brought in the press, and showed his support for a free and independent Georgia and his support for Saakashvili. When the press moved out, President Bush went up to Saakashvili and said putting his finger to his chest, “now don’t you provoke Russia. Because you cannot handle Russia and I cannot protect you from Russia because of the geography.” So, it was again, President Bush both trying to show our support for Georgia, but also trying to avoid anything that would provoke or give Putin any excuse for invading Georgia. So, the President was trying to do both of those things but he was very clear with Saakashvili not to provoke the Russians, not to provoke Putin.

Secretary of State Condoleezza Rice visited Georgia about a month before the war. A few American and Georgian officials confirmed that during that conversation Secretary Rice advised President Saakashvili once again not to provoke Russia. Otherwise “he would be alone,” and “it would be the end of him.”

Not “on your own” in the sense that we did not care and that we would have abandoned him, but simply the reality was that it would be very difficult for us to prevent Russia from doing what it did. That was very consistent with the policy that the President had articulated to Saakashvili earlier. Condoleezza Rice, as the Secretary of State, went to reinforce that message with Georgian authorities. And that is exactly what happened.

What do you make of all that? President Bush, Secretary Rice, I am sure you in your meetings with Georgian officials, you all had the same message to convey. Why were you repeating over and over again that Georgia should not have provoked Russia? What was it that kept prompting you to repeat this message to Saakashvili at such a high level? What was it that he was doing?

You do that all the time. Leaders are usually strong-willed individuals. That was true of Saakashvili as you would expect – young, aggressive, self-confident person, who had done wonderful things for his country. When you are in a situation like that, it is very frequent for you to keep repeating the message to make sure that it gets through. Secondly, it was important because in the run-up period, Russia was doing a number of things that could have been read as provoking Saakashvili. So, it was to reinforce a message said with great respect but with great seriousness to a friendly country. It was also important to reinforce that because Saakashvili was being provoked by the Russians and it was very important to calm him down and not have him respond in a way that he would regret in retrospect.

Do you think the war was inevitable?

You can probably say that there is a way to avoid most wars with the benefit of omniscient hindsight, but that does not mean that with the limitations of foresight, you would necessarily act on it – you know, wars happen and nobody likes them, but they happen nonetheless.

There was often criticism towards your administration that you did not understand Russia, the Kremlin, and President Putin. Secretary Rice was particularly perceived as a person who was the most knowledgeable of Russia. However, in the end, it turned out that the administration did not fully understand Russia’s intentions. What do you think – how well did the Bush Administration knew Russia?

I think we understood Russia quite well. We had tried to engage Russia. We had tried to encourage Putin to understand that he had an opportunity to bring Russia permanently into the West – to affiliate with western institutions. We had encouraged him to have a positive relationship with the EU. We had encouraged him to have a positive relationship with NATO. We had the NATO-Russia Council. We did a lot of things. We offered to do cooperative ballistic missile defense with Russia to treat them as a strategic partner.

I think in retrospect it was the color revolutions that derailed our relations. Putin got it in his head that America was behind the color revolutions – that the NGOs and all the rest were in fact tools of the American CIA.

This was of course not true. The objective was to establish free and independent governments, which is what we wanted to do, because we think free and independent governments are good neighbors. But Putin read that as trying to establish governments that would be hostile to Russia. Some people think that he thought the color revolutions in countries that were on Russia’s border were a dress rehearsal for a color revolution in Russia itself.

That was not American policy. We were not behind the color revolutions. It was the people of these countries themselves. But that is not how Putin saw it. He saw it as a threat to Russia. I think that was the problem. That is where Russia and Putin sort of changed their policy and became increasingly hostile to and suspicious of the West. The invasion of Georgia in 2008 was in some sense a fulfillment of his transition.

When he went into Georgia, as we thought about how to respond, our goal was to try to show that Putin paid a strategic price for doing that and tactically gained nothing out of it. Why did we want to do that? Because our concern was – if we did not establish those lessons clearly in Georgia in 2008, as we said at the time, next will be Ukraine and after that will be the Baltics. We were concerned that Putin, if he succeeded, would feel so enabled and empowered, he might try to get into Ukraine and ultimately in the Baltic states. And of course, if he did it in the Baltic states, since they were members of NATO, that would mean the NATO-Russia war, something nobody wanted.

Are you saying that you made Russia pay a price?

We did a number of things. As you know, we moved a destroyer into the Black Sea. We helped airlift Georgian forces from Iraq back to Georgia. We delivered assistance in military aircraft to try to send the message that this was something that threatened a wider confrontation with Russia. As you know Condoleezza Rice famously outed Sergey Lavrov when Lavrov told her his objective was to overthrow the Saakashvili government and take Tbilisi. She went public and tried to establish that it was a red line and I think in some sense, it did deter Russia from going further.

As it comes to economic sanctions, the problem was that this was followed very quickly by the economic and financial crash of 2008, which made it very difficult to impose financial sanctions against Russia. So, in conjunction with our allies, we stopped relations with Russia, the NATO-Russia Council, we tried to throw the U.S. and European relations with Russia into the toilet in order to make a statement to Putin and to Russia that this was unacceptable behavior and contrary to all the understanding which have been developed at the end of the Cold War as to what would be the premises and foundations of security in Europe, which foremost was to respect the sovereignty of states, and no use of force or threat of force against your neighbors and certainly no invasion or changing borders by force. And Putin’s action in Georgia violated all those principles.

Despite everything you just listed, we could still say that tougher actions could have been taken. The U.S. was getting ready for a presidential election in November. After the Bucharest Summit the administration had virtually no political capital left with the allies. Possibly for these and other reasons the western reaction to Russia’s invasion in Georgia was fairly weak. What do you think – did this weak response encourage Russia to invade Ukraine a few years later?

No one can know. I think we did as much as we could, considering it was the end of administration. We were in the biggest financial and economic crisis since the Depression. There were a lot of distractions. I think if we had had our way, we would have argued that the Obama administration and the Europeans should have kept the actions that we had put in place longer – should have kept the U.S.-Russia relations and the European-Russian relations in the deep freeze for a much longer period of time, as we have, quite frankly, in the wake of Ukraine.

For its own reasons, the Obama administration decided to have a reset of the U.S.-Russia relations and that resulted in the rollback and the reestablishment of ties with Moscow. No one will know whether a different policy would have resulted in deterring Russia from doing what it did in Ukraine. My own view is that what happened in Ukraine was a function of a lot of what happened on the ground in Ukraine.

French President Nicolas Sarkozy at the time mediated the ceasefire agreement. The so called Sarkozy Agreement has 6 points, which to this day are not implemented. What do you think about this agreement?

Well, let us not ignore what was accomplished in that ceasefire agreement. What we worried about was that the road to Tbilisi was pretty much open to Russian tanks. Russia could have easily gone and overturned the government and taken control of the country. Now, that did not happen and therefore, Georgia is today an independent state with a robust economy and a reforming political process. And yes, the Russian troops are in Abkhazia and South Ossetia, but as you know, they were in Abkhazia and South Ossetia before the invasion. So, let us not be too quick to dismiss what was achieved in the ceasefire.

What do you think Georgia should do at this point? Now that Putin was reelected for his fourth presidential term and when the Kremlin is doing everything it can to have other countries recognize Abkhazia and South Ossetia as independent countries?

I would say to our Georgian friends, the most important thing Georgia can do is to build its state and build its society and build an economically prosperous and vital democracy in Georgia that is supported by the people of Georgia and can be an example in the region and particularly, to the people in South Ossetia and Abkhazia. I think at some point when Georgia does that, the people of South Ossetia and Abkhazia may decide that being part of Georgia is a lot better deal than being under the thumb of Russia. From the information I have, things are not particularly attractive in South Ossetia and Abkhazia as a place to live. At some point we hope that the people in those areas will think maybe they have made a wrong choice. But I think what Georgia needs to do is exactly that: build Georgia into the kind of society that your people deserve and your people will support.

This material was prepared for Civil.ge by the Voice of America. In order to license this and other content free of charge, please contact Adam Gartner.

This post is also available in: ქართული (Georgian) Русский (Russian)