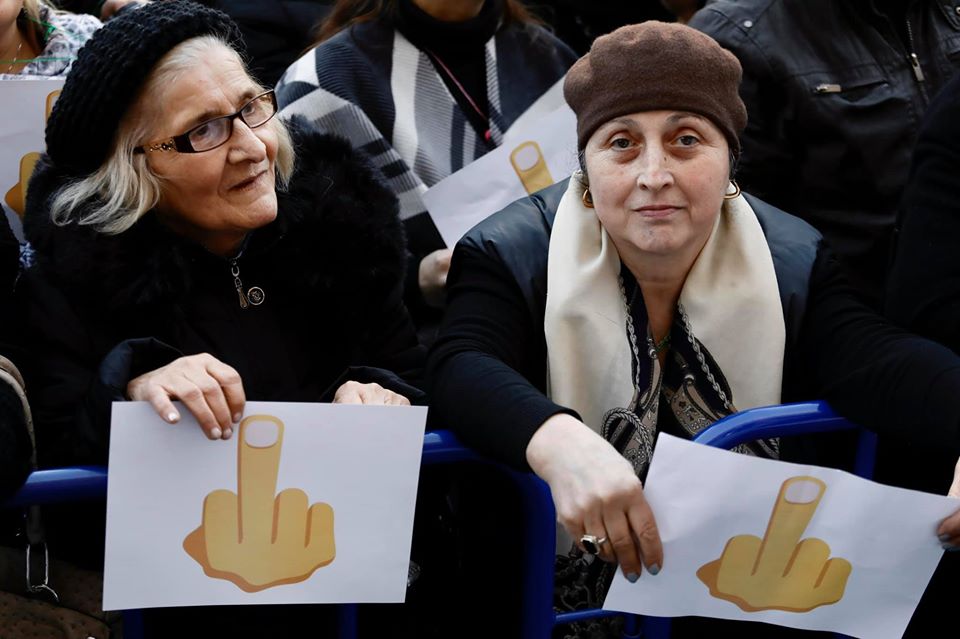

Political crisis has once again spilled onto the streets in Georgia. The decision of the ruling Georgian Dream (GD) to bin the promised proportional polls has inflamed passions, but no negotiated solution seems in sight. We have asked long-time Georgian observers, Ted Jonas and William Dunbar, what do they see as the potential way out:

Ted Jonas:

I think Georgians need to simply prepare for elections. There are two ends on the Georgian political spectrum that I personally don’t care for, because neither is democratic nor committed to the rule of law.

On one end is the Georgian Dream party, now stripped of nearly all its moderates. Even further out beyond them are right-wing religious and nationalist forces. On the other end is Misha Saakashvili and the part of the United National movement (UNM) that remains committed to him.

What I think Georgians should work on today is building up the political parties that stand between these two poles, and building relationships between parties that will allow the formation of electoral blocs, now that we are back to having a threshold for entry into Parliament, parties committed to democratic participation in governance and to rule of law. In other words, liberal democracy.

The spectrum of parties and voters that believe in these ideas run from GD moderates through long time centrists like the Republicans and Free Democrats, to new centrists like Khazaradze’s LELO party, to UNM and former UNM moderates, such as European Georgia, other refugees from the UNM, and some still in the UNM.

Whether youth activists or party hacks, these politicians and activists need to be out meeting voters and working on building a base. They need to be reaching out to business and building support from people with money to contribute to political parties. They should be running small meetings and workshops.

I do not believe that continued standing around in the street will accomplish much. What’s needed is developing policies that address the country’s problems – employment, social welfare, education, the environment – recruiting and putting forth talented politicians who can learn about and advocate for such policies convincingly for voters, and putting together the pieces needed to win elections.

I don’t see any purpose at all in continued dialogue between the opposition and the ruling party – the ruling party has already shut the door on that, shown it isn’t interested in it, and shown it can’t be trusted; it is as useless as standing in the street. People need to just prepare for elections and work to win them – for their parties and their coalitions.

William Dunbar:

Almost four fifths of Georgians support the change to a proportional system, according to a recent IRI poll. But the main issue here is not the electoral system: it is the sheer mendacity of Bidzina Ivanishvili. He has lied to the Georgian people, lied to Georgia’s western partners, and even lied to key leaders within his own party. He is not an honest broker; there can be no deal making with him.

And, as Georgian Dream continues to haemorrhage support—why would the opposition want to treat with him now? The IRI poll show support for GD at 23%, a margin of error higher than the UNM and its offshoot European Georgia, on 15 and 5% respectively.

More than a third of Georgians say they don’t know who they support, a suspiciously large number, which, in an echo of the 2012 election, most likely hides many more opposition supporters.

Thus, regardless of the election system, Ivanishvili and GD are in serious trouble, and it is this which poses such a risk to the future of the country.

Ivanishvili holds scant regards for democratic norms, as we saw in 2018 when he deployed bribery, violence and intimidation to secure the presidency for ‘independent’ candidate Salome Zurabishvili. He is likely to double down on these tactics as we approach the next election. The opposition, divided and sometimes irresponsible, risks playing into his hand by flirting with violent tactics.

Ivanishvili’s government has shown no qualms about jailing opposition leaders in the past, there is no reason to suppose it won’t do so in the future.

By lying repeatedly to Georgia’s western allies (over Anaklia as well as electoral reform), Ivanishvili has strained relations already; he is unlikely to care too much about western censure over increasing repression. Indeed, tensions with the west might be replaced by an improved relationship with Russia, a country which is much less concerned about the conduct of elections.

The 2020 election was always going to be bitter, divisive and destabilizing, but, by reneging on his promise to hold the elections under a fully proportional system, Bidzina Ivanishvili has pushed the country to the brink of a serious crisis.