“Some doctors are paid 300 Laris [USD 97] a month, while others get 120,000 [USD 39,000],” Georgian Health Minister Ekaterine Tikaradze reported to the Parliament early in 2021, hinting she wanted to do something about it. “You will probably agree this is unfair.”

In social media, medical workers and their advocates – happy that someone at the top finally saw the unjust treatment – went to embrace her remarks. Private clinic heads, on the other hand, reacted with confusion, questioning both the fairness of criticism and the government’s ability and right to interfere with the status quo.

But the hopes now look dashed. With the Minister having announced her departure on December 9, thanking in her farewell address nurses and doctors for their tireless fight through the pandemic, one could see little being done over the months to address the health workers’ concerns over fair pay and conditions.

Heroes Treated Zeroes

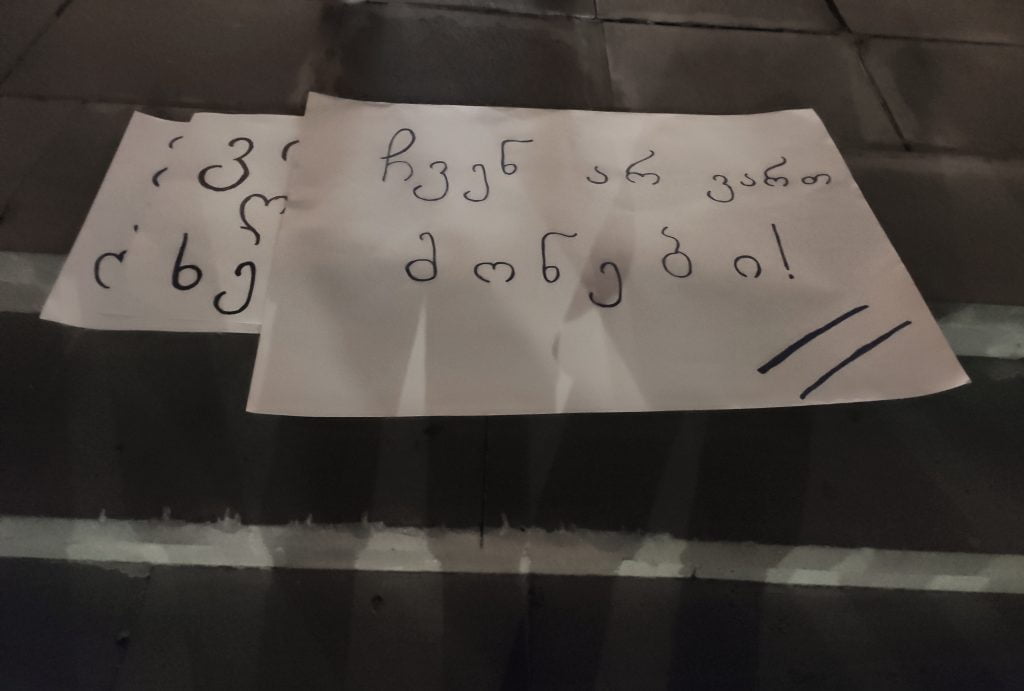

Some 24 hours after Tikaradze announced her resignation, a small but long-planned demo took place in front of the Government Administration building in downtown Tbilisi. A handful of nurses and activists demanded dignified compensation and labor conditions. The participants could not think of any steps forward in this regard over the past months and years, despite many “thank yous.”

In March 2020, at the onset of the pandemic, many Georgians went to their balconies for mass applause to show appreciation for frontline doctors and nurses. By then, Georgia had recorded a total of mere 38 COVID-19 infections in a few weeks. There were lots of regretful talks at the time about the country finally seeing the light and giving the overworked and underpaid health workers credits they deserved.

As months went by, daily cases soared to reach 4-5 thousand, hospitals got overcrowded, and health workers have become more overworked than ever, repeatedly risking and losing their lives.

But the attitudes slowly went from clap to slap: medics now faced more anger than gratitude as COVID-deniers or lockdown opponents started looking for scapegoats to explain dozens of daily deaths. As the narrative of doctors as main villains in the public health disaster grew stronger, the health workers were again left alone in their struggle for dignified labor conditions, with few jumping to their defense.

A Long List of Complaints

Now and then, through activist networks or media, concerns of medical workers – and particularly nurses or their assistants – leave remote hospital wards to see the daylight.

A lengthy list of complaints includes poor labor conditions with even poorer compensation, often far below USD 100 per month; nurses face heavy workload that only got worse amid pandemic, and salaries are often delayed for months or even for years; many work several jobs and double shifts to make ends meet, leaving little to no space for personal lives.

This sometimes comes with humiliating attitudes from the top, no lunch breaks, and burnouts impacting their own health. And then there is a lack of a safe working environment, with some of the nurses contracting COVID more than once.

Tikaradze said she will remain in her position till the end of the year. Disagreements with the rest of the government and the inability to push desired policies are rumored to have contributed to her decision to quit. So even if there indeed was a will to do something, the question is how much there were ways to follow through with it.

Sopo Japaridze from the Solidarity Network, an independent labor union uniting service and care workers, which organized the protest, told Civil.ge at the demo that the authorities may be afraid to confront employers.

“Imagine what employers will do if [the government] makes them triple the salaries for nurses,” she says, recalling other recent spats between the authorities and powerful private sector over regulations. “For now, they are more afraid of employers than they are of employees.”

(No) Hopes for Change?

2021 turned out to be a particularly successful year for collective action in Georgia — with workers from Borjomi to Tbilisi-centered gig economy regularly winning through strikes. Not for nurses. Aside from the serious consequences and responsibilities attached to strikes of medical workers, the fear also prevents them from turning to less radical forms of protests.

Japaridze says the nurses are scared of losing even their lowest wages and then being unable to find a job in other hospitals due to their protest record, something that stands in the way of larger organizing.

So far, sporadic small-scale rallies are not doing the job, and nurses have to settle for about one-fifth of USD 500, a gross monthly income which, according to calculations made by Solidarity Network, is necessary to live a dignified life in Georgia.

The number of health workers in the country is estimated at around 75,000. But if the daily grind of a group this large goes unnoticed even as the country slides into the third year of the pandemic, what are their hopes that the situation will ever change for the better?