The mood was solemn on 30 July at a dilapidated house in central Tbilisi, as speaker after speaker from Soviet Past Research Laboratory (SovLab), a think tank, read to a small crowd the endless names of the men and women killed by the Soviet terror machine in 1937-38.

The setup is meaningful in its detail. The house in question, located at Ingorokva st. 22 used to house the headquarters of the infamous CheKa (Russian abbreviation for чрезвычайная комиссия, Special Commission) – a precursor to the feared NKVD, later KGB. It is in these halls and cellars, that thousands were tortured and killed. The date – 30 July – marks the appearance of the NKVD Order 00447 in 1937, which created extra-judicial tribunals, known as “Troika”, and opened the gates to the particularly bloody wave of terror which ended or maimed the lives of hundreds of thousands in Georgia.

For years now, SovLab has been campaigning to mark 30 July as the day of memory for the victims of Stalinist terror. So far, their demands have fallen on the deaf ears of the government. Conceived as a research organization, SovLab has been scouring state and private archives to establish the truth about those who perished during those years.

But Giorgi Kandelaki, a former journalist who served as an MP from 2008 to 2020, who came to SovLab to pursue his longtime professional interest in recent history, says “we have realized…that analyzing each and every lie in a sophisticated academic manner may be interesting but that it is not really doing much harm to the actual disinformation that has flooded our society.” Hence, the renewed efforts to engage more actively in education and activism.

The Trail of Blood

The number of Soviet terror victims in Georgia is staggering. Researchers estimate, that from 1921-1953, twenty thousand were executed. Hundreds of thousands were deported, and tens of thousands were sent to infamous camps. The number of those who died in preliminary detention facilities, during brutal interrogations remains unknown.

Georgia has seen several waves of Soviet terror. The first to be mowed down were the officials of the Democratic Republic of Georgia (1918-1921) which Soviet Russia occupied with military force only a year after having signed a peace treaty with Tbilisi. Out of 108 members of the Constituent Assembly (the parliament) that remained in Georgia after the occupation, 51 were executed by 1950, five more died in camps, and 37 more were arrested or deported. The fate of the military and security officers was even graver: three thousand were killed after their uprising was brutally suppressed by the Soviets in 1924.

As elsewhere in the Soviet Union, their executioners soon became victims, as Stalin got on with the job of eliminating dissent within the party. Eleven thousand people were executed in Georgia in 1937-38, during what is known as the Great Terror. Many were yesterday’s influential communist leaders, actors, writers, but also simple workers who fell victims to the wave of denunciations.

Resurgence of Stalinism?

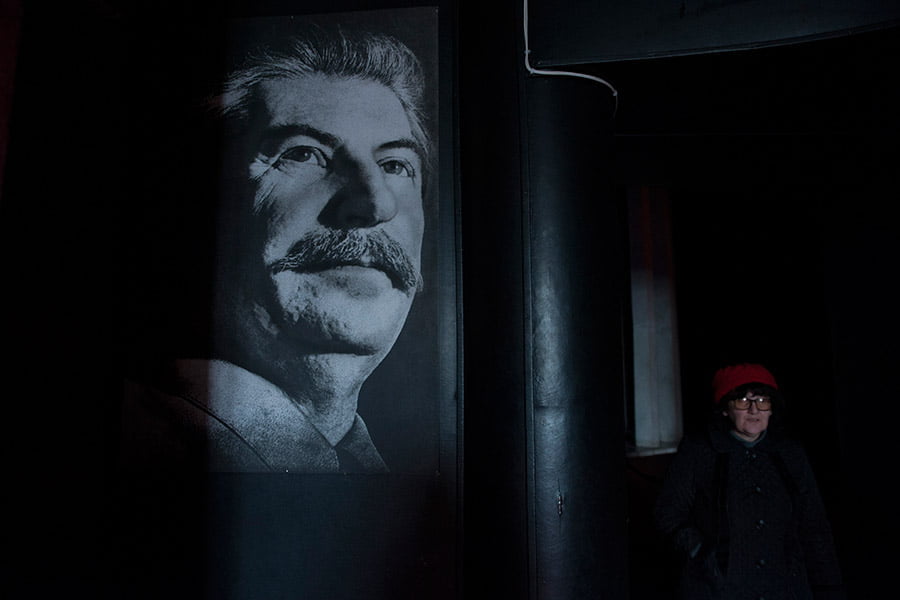

Irakli Khvadagiani, one of SovLab’s key researchers, tells us with concern that in the past ten years, 11 new statues of Stalin have popped up around Georgia. Sometimes, the effigy of the mustachioed tyrant is brought back by private persons on their property, others are erected by openly pro-Russian groups. But most worryingly, some statues have been erected at the initiative of local government officials in public spaces, such as village or town centers and at World War II memorials.

Curiously, back in 2013, the Parliament of Georgia adopted changes to the 2011 Liberty Charter, which aimed at creating enforcement measures to prevent the public display of symbols of the totalitarian communist regime. Nonetheless, the trend seems to have been reversed.

A representative sociological study conducted by CRRC Georgia, a pollster, in 2021 showed that 66% of those surveyed agreed with the statement that “Stalin was a wise leader, who brough strength and prosperity to the Soviet Union”. Still, 52% agreed that “Stalin was a tyrant, responsible for the death of millions of innocent people.”

A conflicted attitude then, fear mixed with pride. Perhaps, this can be explained away by the fact, that Stalin was a native of Georgia?

Kandelaki takes a grim view of this oft-repeated justification. To him, there is a more sinister side to Stalin’s rehabilitation in the minds of Georgians, than, for example, the Corsican’s continuous adulation of Napoleon. “How Stalin is viewed by Georgian society is not just the curious academic question of history, but very much the political question of tomorrow”, he argues.

Eto Buziashvili, who researches disinformation at the reputed Digital Forensic Research Lab (DFRLab) of the Atlantic Council, a US-based think-tank, says glorification of Stalin has been a consistent strand of Putin’s narrative. “Since coming to power,” she argues, “Putin has led the effort of creating a cult of personality around Stalin. To justify Putin’s authoritarian rule and aggressive actions in both foreign and domestic affairs, the Kremlin media has attempted to draw a parallel between the Russian president and the Soviet dictator.” In this sense, she feels, Georgians’ affinity to one of their most controversial compatriots is doing them a huge disservice, by making them more vulnerable to Russian neo-imperial propaganda.

Khvadagiani agrees: “As Russia’s war in Ukraine has once again shown, the weaponization of soviet totalitarian history is a key driver of Russian aggression. In fact, that war is very much about the memory of the Soviet Union. While Russia applies the same strategy to Georgia, here it has more often than not focused on pushing Stalin into Georgian nationalism, or rather “nativist” anti-western strait of it that the Kremlin and its proxies have tried to cultivate here over the time.”

“Anyone who thinks that one could be even a little proud of Stalin just because of his Georgian roots is a natural target in the ongoing information warfare,” echoes Kandelaki.

Ignored menace?

SovLab researchers tell us, that the phenomenon of Stalin’s insertion into Georgia’s nativist narratives as a secret patriot, or even a secret defender of Orthodox Christianity is a potent driver of Russian influence, which has been left largely unaddressed by the efforts to combat Russian disinformation.

Buziashvili says the Kremlin’s effort to promote Stalin is not aimed directly or exclusively at Georgians, but “the Kremlin is exploiting our weaknesses – that the society is not well-aware of Stalin’s and Soviet regime’s crimes – and is fueling our sentiments towards the Soviet past.” One of the activists at the event says some people involved in counter-disinformation campaigns have never even heard of the Molotov-Ribbentrop pact – a secret deal to divide Europe between the Nazi and Soviet regimes.

“Weaponization of Soviet experience and Stalin in particular [by Russia] is a terrific way to amplify their messages to broader society while western-funded counter disinformation efforts are largely confined to narrow elitist discourses that mostly bypass broader society. Worse, more often than not, they never even touch upon the “engine” of the disinformation – the Soviet Union,” says Kandelaki.

And while around 80% of Georgians keep responding to polls in support of the country’s European path, historians say this figure may prove more shallow than it looks. Khvadagiani says “if one digs deeper, there is very little ground for complacency and the resurging support for Stalin is dangerous proof of that.”