Abkhaz Decision on Passports Leaves Many Georgians in Gali Worried

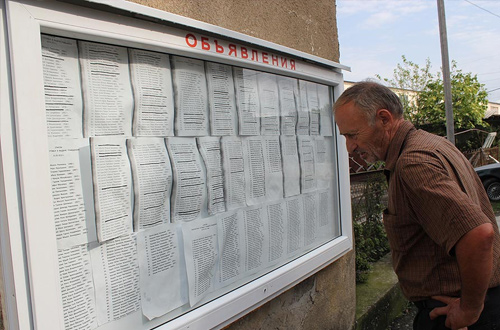

August 2012, outside the Gali passport office, a man from the Georgian village of Saberio (upper part of Gali district) checks if his daughter-in-law was granted Abkhaz ‘citizenship’. Photo: Olesya Vartanyan / RFE/RL’s Ekho Kavkaza

Thousands of Georgians living in breakaway Abkhazia are in tense anticipation of being deprived of their Abkhaz ‘passports’, which, if implemented, will further increase their legal defenselessness and restrict their ability to move freely across the administrative border.

The breakaway region’s Parliament adopted with overwhelming majority on September 18 a resolution instructing the prosecutor’s office to carry out in coming months a “sweeping” probe into passport offices of the interior ministry and, in case of revealing wrongdoings in distribution of passports, to refer these violations to the ministry of internal affairs for the purpose of “annulment of illegally issued passports.” Prosecutor’s office has to present before the Parliament its first report about the probe by the end of this year.

The resolution was a result of a four-month probe by Parliament’s investigation commission, which was studying whether passports in Gali, Ochamchire and Tkvarcheli districts were issued in compliance with the law.

The commission, which laid out its findings during the much-anticipated parliamentary session on September 18, said that “significant number” of residents of Gali, Ochamchire and Tkvarcheli districts received Abkhaz passports while at the same time retaining their Georgian citizenship, which constitutes violation of law on Abkhaz ‘citizenship’.

Over 46,000 Georgians live in Abkhazia, according to 2011 official Abkhaz census; vast majority of them reside in the Gali district.

According to the Abkhaz officials, more than 26,000 passports were distributed in Gali, Tkvarcheli and Ochamchire districts, including about 23,000 of them were given out since Russia’s recognition of Abkhazia in August, 2008.

Abkhaz document allows locals to move easily across the administrative boundary line on the Enguri river to the rest of Georgia. Since 2009 holders of the Abkhaz passports can also travel easily to Russia and stay there for three months without registration. Locals in Gali say that it even attracted some Georgians from outside Abkhazia to arrive there and get Abkhaz passports through bribing local officials in order to get an easy entry to Russia, which unilaterally maintains visa requirements for the Georgian citizens.

Like many other Georgians in the Gali district, a 39-year-old local resident, Nana, fears that the Abkhaz Parliament’s resolution will lead to stripping of her Abkhaz passport, because she also retains her Georgian ID, which allows her to have an access to services available on the Georgian-controlled side of the administrative border.

Nana, who lives in a small house in the Gali district with her three children, says that when two years ago she at last received her Abkhaz passport after several months of going back and forth between her village and local passport office in the town of Gali and spending several nights outside that office in order not to lose her place in a long queue of applicants,she felt relieved.Nana, who had to flee her house in the Gali district twice over the past twenty years – first as a result of conflict of early 1990s and then because of 1998 armed clashes, says that Abkhaz document was demonstration of Sokhumi’s readiness to “accept us as citizens”, giving her a sense of security that she would never be forced to leave her home village again.

She recalls that when she filed an application for the Abkhaz passport, she also signed a document renouncing her Georgian citizenship, handing over her Georgian ID to a local official from the passport office and watching how the official was destroying it. But she knew it was a mere formality. “And the official knew that too,” she says.

It took her a day to restore her Georgian ID in the town of Zugdidi on the Georgian-controlled side of the administrative boundary line.

In 2005, citing the need to integrate residents of eastern districts of Abkhazia, then leadership of the region showed signs of softening stance towards granting of citizenship to the residents of Gali, Ochamchire and Tkvarcheli districts. Three commissions were formed, one for each of the three districts, in charge of issuing passports. Parliament’s September 18 resolution orders to disband these commissions.

It remains unclear yet precisely how the process of reviewing passportization will proceed and how many people may lose their documents. The Parliament’s resolution leaves room for the prosecutor’s office to either opt for a time-consuming, case-by-case approach, reviewing each and every case separately or to recommend the interior ministry to annul already issued passports all at once.

A civil society activist and a former member of the Abkhaz Parliament Batal Kobakhia says that case-by-case approach will be more fair.

Speaking at Sokhumi-based Abaza TV’s talk-show on September 19 Batal Kobakhia said if the parliament commission had revealed that only “1,000 passports were issued illegally, that should not mean that the rest 26,000 have to suffer.” In the televised discussion he also raised the issue of responsibility suggesting that the burden should be upon those officials who were involved in this alleged illegal passportization not on ordinary citizens.

Earlier this year the process of “passportization” came under scrutiny of the Abkhaz opposition groups, who turned this issue into one of the central topics of the breakaway region’s internal politics; issuing of passports was suspended in May.

Ten opposition parties and organizations formed the Coordinating Council and launched in the middle of the summer series of rallies across Abkhazia.

In an attempt to mount more pressure on the authorities, some opposition leaders and veterans of war had even threatened to boycott a planned parade on September 30, marking 20th anniversary of victory against the Georgian forces, in case they refused to support opposition’s demands.

Opposition claimed that “massive” passportization, involving granting citizenship to ethnic Georgians in eastern Abkhazia, was fraught with risk of “losing sovereignty and territorial integrity.”

Similar sentiments were also voiced during the parliamentary sitting on September 18, reflecting not just a political view of any particular opposition group, but also still persisting sense among broader Abkhaz society that ethnic Georgians of Gali might be used by Tbilisi to destabilize Abkhazia from within. Another key aspect is that authorities in Sokhumi view this long-standing issue of passports and citizenship as a pressing problem that needs to be tackled in the “state-building” process.

Head of the parliamentary investigation commission, MP Aslan Kobakhia, a veteran of the armed conflict of early 1990s, told the session on September 18 that there was a threat Georgian government could use its citizens living in eastern districts of Abkhazia to provoke a new war.

“We know about 129 [Georgian] guardsmen [referring to those who fought against Abkhaz forces] are wishing to get Abkhaz passport,” Kobakhia told MPs. “And many others [who are already Abkhaz citizens] are just waiting for order from the other side of the Inguri river.”

MP Kobakhia is a member of the opposition party the Forum of the National Unity of Abkhazia, led by MP Raul Khajimba, who sponsored a bill tightening Abkhaz law on citizenship.

Both the resolution and amendments to the law were passed on September 18 in the 35-seat Parliament with 33 votes; two lawmakers abstained. The bill on toughening law on citizenship was signed into law by Abkhaz leader Alexander Ankvab on the same day.

Meanwhile, outside the Parliament, up to 1,000 opposition activists were rallying on September 18, demanding stripping ethnic Georgians of their Abkhaz passports. The Parliament’s resolution was met with jubilation by the protesters, who were chanting: “Victory.”

“All we want is to have order. We want our state to succeed. That’s exactly what we have fought for – independence of our state,” Khajimba told supporters at the rally. “It doesn’t mean we have blood lust. We don’t want this [war] to reoccur in the future.”

About the author:

Olesya Vartanyan is a reporter of RFE/RL’s Ekho Kavkaza