Commentary: Georgia-China relations are about more than economics

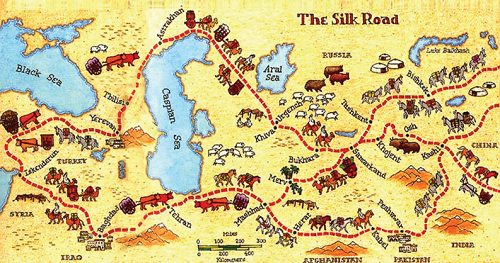

Photo: The Silk Road Project. Permission for use guaranteed to the Georgian Institute of Politics

China has shown a growing interest in Georgia. Cooperation is largely confined to the economic sphere. However, a stronger Chinese presence in the context of the Belt and Road Initiative could have major geopolitical significance.

Georgia-China ties have advanced continuously since China officially recognized Georgia in 1992, and especially since 2009. Cooperation is mostly confined to the economic sphere, where China is an important trade and investment partner. Through the first eight months of 2017, China was the number-two consumer of Georgian wine, after Russia, and the third-largest consumer of Georgia’s exports overall. The two countries signed a free trade agreement earlier this year, which is expected to further expand the market for Georgia’s exports. Investment is also important. In 2014, Chinese companies invested USD 217 million in Georgia’s economy, more than in all previous years combined.

There is also potential for stronger diplomatic and strategic ties due to Georgia’s involvement in the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI).

The Belt and Road

A new player in the region, China views Georgia as part of the BRI, a project designed to “shorten the distance between China and Europe” through improved infrastructure connections. The Chinese government first announced the initiative in 2013, calling it the “project of the century” and pledging to invest USD 150 billion each year in related projects. And that’s just part of it. The initiative currently involves 68 countries accounting for more than 60% of the world’s population and nearly one-third of global GDP. Multilateral development banks and private investors are also putting up money. According to a report from Fitch Ratings, roughly USD 900 billion in related projects are currently planned or underway.

The Belt and Road is divided into two sides, one covering overland routes and the other covering sea lanes. The Belt – officially named the “Silk Road Economic Belt” – is the land component. It includes six corridors designed to better connect China to Europe through Central and West Asia. The Road – short for the “New Maritime Silk Road” – is the sea component, designed to connect Asia to Europe through new ports in South Asia and East Africa.

Georgia is participating in the Belt through the China-Central Asia-West Asia Corridor, one of the six corridors making up the Belt. The corridor runs from China across Kazakhstan to the Caspian Sea. From there it splits in two—south to Iran, and across the Caspian to Azerbaijan. From Azerbaijan it goes onward to Georgia, Turkey, Ukraine, and Western Europe.

Georgia became directly involved in the BRI last year when it joined the Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank (AIIB), a USD 100 billion bank designed to funnel money into BRI projects. This year, Georgia signed an agreement by which the bank will provide USD 114 million to build the Batumi Bypass Road. Also in 2017, the two countries signed a free trade agreement which will strengthen Georgia’s position as a hub between Europe and Asia.

It’s important not to overstate Georgia’s importance to the Belt and Road. Alternative transit corridors pass through Russia and Iran, so the initiative could go ahead without Georgia’s involvement. Still, the country has a lot to offer. It has improving infrastructure connections with Ukraine and Turkey. It is the only country in the region that has a DCFTA with the European Union. It has a predictable regulatory environment.

Georgia offers an alternative to Russia, which has poor infrastructure and public policy and is in the middle of a trade war with the EU. It also offers an alternative to Iran, which is still an international pariah and has poor relations with its neighbors. Georgia won’t be a main actor on the Belt and Road but can still play an important part.

When Business Turns Political

The Chinese government has been careful to frame the BRI using politically-neutral language. Official documents emphasize its potential to achieve such benign goals as “peace, development, cooperation and mutual benefit.” In 2015, Chinese Foreign Minister Wang Yi stated the initiative was “not a tool of geopolitics.” However, Georgia-China relations could potentially have a geopolitical component. As China becomes more engaged with Georgia and other countries in the region—and as the region becomes more integrated into the Belt and Road – China will have a greater interest in maintaining regional security and stability. That has major implications for Russia, which constantly threatens Georgia’s security.

Russia is heavily dependent on China as a source of investment, import and export market, and provider of diplomatic backing. That gives China a tremendous degree of leverage. If Russia threatened Georgia with a new military escalation, China could potentially play the role of disciplinarian, using its financial power to deter Russian aggression. For example, China could threaten to cut off investment to Russia or to other members of the Eurasian Economic Union, or restrict trade. At the very least it could provide an implicit check on Russia.

It is also worth noting that Georgia and China already have the foundation for closer diplomatic ties. China supported Georgia diplomatically after the 2008 war. Despite Russia’s best efforts, China and its partners in the Shanghai Cooperation Organization (SCO) refused to recognize Abkhazia and South Ossetia as independent states back in 2008. China has strongly supported Georgia’s territorial integrity since then. And while Georgia isn’t a member of the SCO, it shares the organization’s emphasis on combatting the “three evils” of extremism, terrorism, and separatism.

While China does not present an alternative to NATO and EU integration, deeper Georgia-China ties have the potential to strengthen Georgia’s foreign policy position. There is little downside from Georgia’s perspective. By engaging with China, Georgia doesn’t risk alienating existing partners such as the United States, the European Union, Azerbaijan, and Turkey. The only potential risk is over-dependence on China, but given Georgia’s close economic relations with its near neighbors, that risk is minimal. In short, relations with China have the potential to complement Georgia’s existing foreign policy.

Joseph Larsen is a policy analyst at the Georgian Institute of Politics. Full policy paper can be found here.