Georgia still remains among “partly free” countries, according to an annual country report on global political rights and civil liberties by Freedom House.

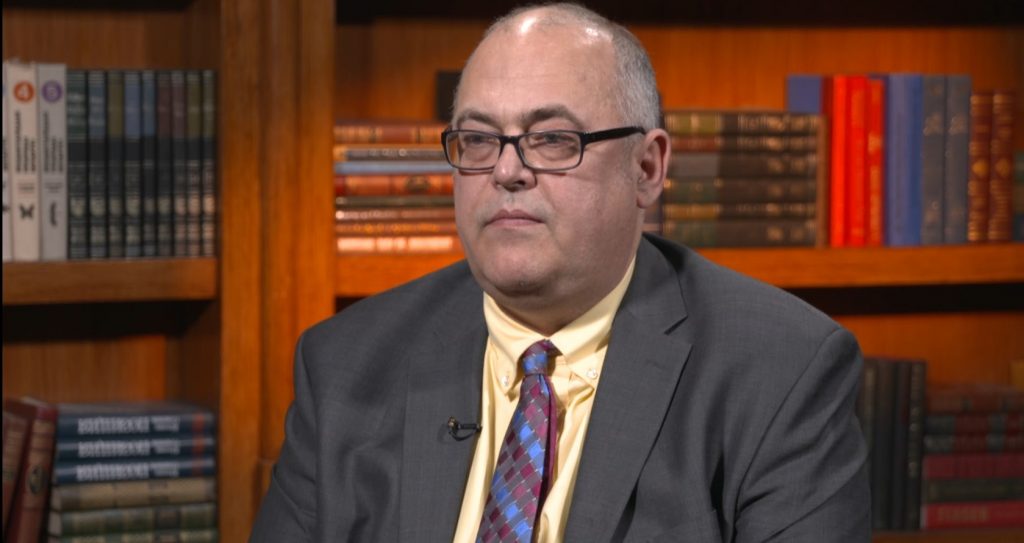

Eka Maghaldadze of the Voice of America’s Georgian Service in Washington D.C. talked to Marc Behrendt, Director of Europe and Eurasia programs at Freedom House, to discuss key findings of the report and challenges facing the Georgian democracy.

Where does Georgia stand in this report? It remains among “partly free” countries, but the score has declined. How much did it decline this year and why?

The score has declined by one point which is quite small and it should not be a cause for massive concern – or delight, or sugarcoating – because they change over time; there were two areas where there were declines and one area, where there was an improvement.

Broadly speaking, declining was around the presidential elections. Over the last few years, elections have been known to be basically pretty good in Georgia, and the country has gotten some very good score ratings. OSCE observation reports have always been very good, compared to other parts of the region.

That was even true up until the second round of the presidential elections. In the second round things got worse. The sense is that there are credible allegations – not that we are saying they are proven – but there are credible allegations that there was vote-buying and use of administrative resources – some of [those] negative things that we have seen over the years elsewhere, as well as in Georgia, in not too distant a past. And this is sad, of course.

The [presidential] elections [were] interesting in Georgia because there really was a competitive contest: noone knew who was going to win. This is not true for many – or most – of Georgia’s neighbors… […] That shows that Georgia has a vibrant democracy.

But the fact that [this] insecurity about who was going to win, might have led some people to not necessarily follow the rules as well as they should have – [that] is something that we should be worried about, and [that] the Georgian people should be concerned about.

Last year, key areas of your concern were consolidation of power and Ivanishvili’s influence on Georgian politics. What are the main issues that contributed to backsliding this year?

One of the biggest problems is not so much whether Bidzina Ivanishvili is a shadow power or not. He is, and that is not good. It is not good, when you have someone who is not elected, having a lot of influence. But that is [now] a fact of Georgian politics.

I think, the underlying problem is that Georgia still has not gotten past the sense of politics revolving around the competition between the Georgian Dream and the United National Movement…[between] Bidzina Ivanishvili and Mikheil Saakashvili.

These are not the only two people in the country, these are not the only two people with ideas about how things can move forward. Georgian politics needs to move beyond these two individuals, [there needs] to be thinking about what Georgia wants to do and what [does it want] to look like in the nearest future.

So I really think that Georgia being caught in the trap of these two people is something that is keeping politics from developing in a more stable and normal way; it is preventing the development of reasonable political parties, it is preventing the development of political parties with strong ideas and platforms that people can actually look [at] and evaluate and decide [whether] this is something that they want to support, or not.

There is no real sense of an ideological discussion, other than the real trope of pro-Russian or pro-West, which I think is not honest; Georgia is committed to its pro-Western, Euro-Atlantic strategy and this is not something that anybody is really trying to undermine.

Yes, there are different strategies how it can be [done] and people can spin that [any way] they want, but that is not the key issue. Key issues are economic and political, how to deal with the economy and who to trade with and how this trading can happen.

There are so many questions that are not being asked by the Georgian political class right now and that is a huge problem.

You mentioned Russia, how do you think, does Russian propaganda and Kremlin’s disinformation pose a threat to the Georgian democracy?

I think, it is a challenge for any democracy. Disinformation and the ability to use social networks and other kinds of platforms to change the political discussion – in an artificial way – is something that we have not really seen in the world up until recently.

During the Cold War, you did not really have western societies being undermined by Soviet propaganda or the Soviet society being undermined by western positions and ideas, but we are seeing this now, and it is very sophisticated and hard to recognize.

So yes, I think it is a challenge for Georgia: the weaker your democratic institutions are and the less sophisticated your population is in understanding of these kinds of misinformation, [the more dangerous it is].

[I do not mean it is not a sophisticated society, it is a very sophisticated society, but] in terms of dealing with this particular problem I think people have to actually work [more]. It is a question of civic education, it is a question for the schools, for a responsible political class to be discussing.So it is a big issue, and not as simplistic as pro-Russia or anti-Russia. It is much more complex.

Georgian government’s verbal attacks on civil society organizations were widely criticized by observers even here in Washington D.C. Was this issue reflected in the report?

I think, the Georgian civil society sector is very strong. They are very well-informed, they are not holding back in their criticism and in their ability to engage on very difficult questions.

I think, it is to Georgia’s credit that civil society is threatening the political elites [to the extent that] it is.

Of course, it is not nice to see personal attacks, it is not nice to see that taking place at the international arena, for example, in Copenhagen.

I do not think that is a good thing, it is not healthy, but at the same time, it is not violence – it is people criticizing [other] people for saying things that they do not like and [those people] criticizing them back.

In a sense it is part of a vibrant democracy to have strong debate. I do not think that civic society is at risk of being smothered, or destroyed, or stifled by this.

It does not really look good on the part of those in power who go to extremes and do these [kinds of verbal attacks], it does not show them in a good light at all.

But it is not threatening the Georgian society and the Georgian democracy in my opinion. Maybe it is, again, a compliment to the effectiveness of civil society.

Georgian government has been critical about Freedom House results last year, even questioning their trustworthiness. This year, one of your colleague’s comments about challenges to Georgian democracy and Ivanishvili’s influence, as well as the presidential elections, were dismissed by some government officials who said Freedom House even had apologized previously for some, as they call “mistakes,” and they imply that, perhaps, your colleagues are misinformed again. How do you react to that?

Freedom house is very transparent about its process, its methodology is open for everybody to look at.

We are very clear about what constitutes the change in scoring points, you can agree or disagree, you can argue the facts – and certainly if we get facts wrong, like anybody [may] – then we need to correct them.

I think, we are basically doing a very good job – over the world, across the board – and in Georgia [as well] in checking the facts and getting them right. So it is a little bit sour grapes, especially for Georgia, which is a country that has done so much and has such a success comparatively across the region, in Europe and in the Eurasia, to take offense and to react in this way.

There are going to be criticisms and strong democracy only gets stronger by engaging these criticisms.

I certainly do not think that it is fair to attack our reports. But anytime you are doing a report like this, you are constantly going to be challenged and this is what is just happening in this case.

What would be the key recommendations for the Georgian government?

[Our] key recommendation is to do whatever you can to engage with civil society as a partner.

Civil society is going to have to be holding you accountable, to the principles of the society that you want to build. But at the same time civil society is an important partner to move forward with any of your reform efforts. Have a strong critical partnership with them.

Certainly, I think the Georgian government – and not only the government, but the Georgian political parties, the political system itself, the political elite – needs to get over this duel between Misha and Bidzina.

Georgia needs to move on; just because you are critical of the Georgian Dream, that should not mean that you love Misha or if you love Misha, that should not mean that everything that the Georgian Dream is doing, is wrong. This is not helpful for Georgia moving forward and trying to figure out how to solve its most fundamental problems.

This material was prepared for Civil.ge by the Voice of America. In order to license this and other content free of charge, please contact Adam Gartner.

This post is also available in: ქართული (Georgian) Русский (Russian)