“Georgia’s Minorities Have Diverging Views on EU, NATO” – Interview with Laura Thornton

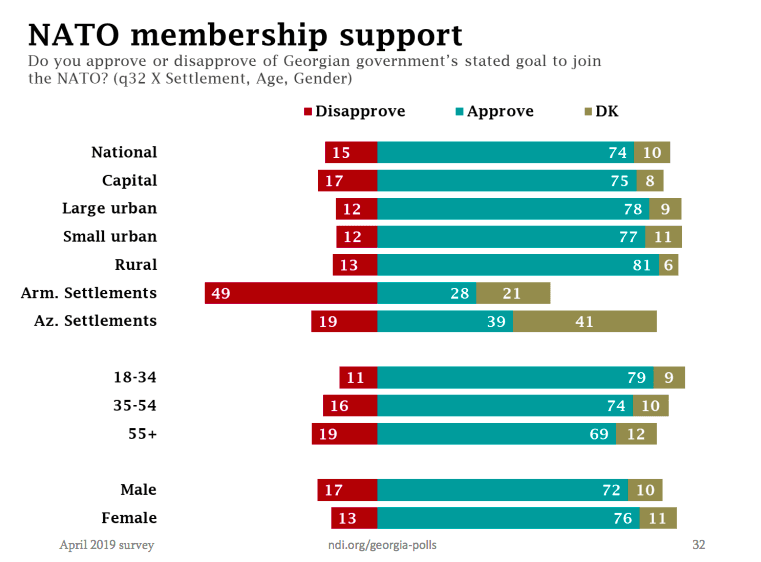

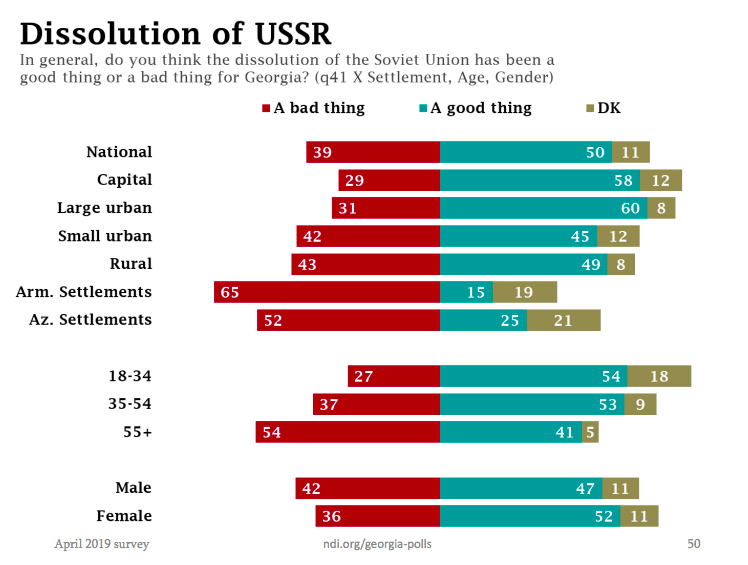

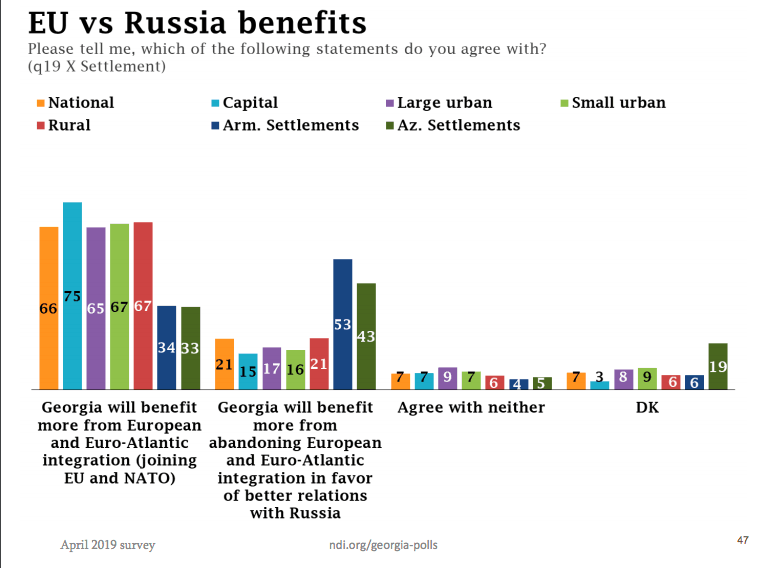

Georgia-watchers have been aware for many years now, largely thanks to NDI/CRRC polls, that compared to ethnic Georgians, Georgia’s largest ethnic minority communities – Azerbaijanis and Armenians – tend to be less supportive of Georgia’s pro-Western foreign policy stance. In April 2019, an NDI poll that oversampled Armenian and Azerbaijani settlements separately found that there are important distinctions between Armenian and Azerbaijani settlements in terms of how they view foreign and security policy issues relating to Georgia. Notably, these results are representative of a trend that has not been identified by previous surveys. Armenians hold strong, opposite views to that of the general population, while Azerbaijanis often “don’t know” or “refuse to answer”.

Civil Georgia’s soliciting editor Otto Kobakhidze sat down with National Democratic Institute’s (NDI) Resident Director Laura Thornton to discuss.

Otto Kobakhidze: For many years we are aware, largely thanks to NDI/CRRC polls, that Georgia’s ethnic minorities hold diverging opinions on country’s integration into NATO and the EU in contrast with ethnic Georgians. What are the main differences we can observe among Georgia’s minorities?

Laura Thornton: There has always been a divergence. Approval for Georgia’s European and Euro-Atlantic aspirations has traditionally been highest in urban areas and among younger people. People from rural areas and minority settlements, as well as the older generation, have been less on board. So, we have known that for some time that ethnic minorities held less favorable views on the EU and NATO. There has, however, been progress over time in minority communities, and approval ratings have grown, particularly for the EU. NATO approval has also increased gradually, or at least disapproval has dropped. In this last poll in fact, we saw, that while approval did not increase, disapproval decreased, replaced by “don’t know” responses. And that’s the first step.

The poll that we did in April is extremely useful because we over-sampled Azerbaijani and Armenian settlements separately to get statistically representative results for those communities. We have always oversampled minority settlements, but as one group. So this was the first time to examine the opinions of Azerbaijani and Armenian settlements separately. And it was fascinating, because we realized that actually the disapproval numbers on foreign policy were from Armenian settlements, while Azerbaijani settlements just do not know. On every question you see high “don’t know” responses from the Azerbaijani community. While Armenian settlements are informed and have strong opinions that are largely against NATO and favorable to Russia. What it indicates to us are significant differences with not only their foreign policy perceptions and views but with their levels of information as well. The reason that is important is that for those who are trying to promote a Western path for Georgia, particularly if you work in the government, NATO, or EU, you need to approach these settlements differently. For Armenians you need to change hearts and minds. That is harder battle in some ways. In the case of Azerbaijanis, you need to provide them with information.

41% of Azerbaijanis don’t know.

Save the historic facts of Armenian-Turkish, Armenian-Azerbaijani, or Azerbaijani-Turkish relations, etc. that might be influencing these views. It would indeed be right to take those historic factors into account. But let’s rather focus on contemporary factors. What are those factors of today that are influencing ethnic minorities’ views about Georgia’s pro-Western foreign policy?

In terms of what’s happening today – I presume a lot is influenced by where you get information. People who are living in Armenian and Azerbaijani settlements do not necessarily watch Georgian television, or listen to Georgian radio, so they are often getting news and information from other sources, be they Russian, Azerbaijani, Turkish, or Armenian. Political and foreign policy views in Armenia and Azerbaijan, for example, are quite different from those of Georgia, and those countries’ paths and relationship with Russia are different. I think that could shape these viewpoints.

However, I would also argue, and particularly in the case of Azerbaijanis as our polls indicate, that there is a very big disconnect for these communities from the rest of the country. And it is not just about the foreign policy. Almost 80% of Azerbaijani settlements have never heard of the Prime Minister of Georgia. That is astonishing. It speaks to this feeling of being left out of the rest of the country. So, if the rest of the country is moving on this particular foreign policy track, these communities have been sidelined.

I also would not dismiss – and this would not affect only those settlements – the role of disinformation campaigns, and some of these campaigns are indigenous to Georgia but a lot of them are from Kremlin and Russian sources. They are planting disinformation about what it means to join the NATO and the EU.

Final point, particularly for Armenians [is that], they don’t see Russia as a threat the way the rest of Georgians do. I would imagine this could be due to historic relationships, and linked to how Armenia sees itself in relation to Russia. In our polls, Armenian settlements don’t think of Russia as a security concern, see Russia as a friend not a foe, and think the dissolution of the Soviet Union was a bad thing. They are not viewing the necessity of NATO as the rest of the population of Georgia perhaps does.

You have lived here in Georgia for quite some time now and you are a close Georgia-watcher. Do you think Georgian leadership is aware of this problem? Would you say, Georgian leaders see this divergence in opinions as a real problem? How would you see Georgian authorities tackling this issue?

I think there are absolutely people in Georgian leadership that are aware of this problem. We work closely with the NATO information center, government bodies, and parliament, for example, and they understand these challenges and are reaching out to these communities, and I appreciate their efforts.

I think one problem is that there is a lack of resources to do a massive education and outreach campaign on foreign policy to the entire population. And among some politicians there is also a little bit of complacency – and our polls sometimes contribute to that by showing such high approval rates for the EU and NATO. It can be tempting to wash your hands and say we are “all good here,” and not take action. We have been advocating that while approval figures are encouraging, it does not mean they are not fragile. For example, a lot of the people who approve EU and NATO membership also hold views that are very problematic, like “I believe the EU threatens Georgian culture and traditions,” or “I believe NATO threatens the [Georgian] Orthodox Church.” So, it is not as simple as approve or disapprove. We need to make sure that people change these other views and misconceptions to stay on this track of European and Euro- Atlantic integration. We also need to be more cognizant that there are forces that are working actively against this path, as I have described. So, my argument is, it’s great, bravo Georgia, you cannot find such figures even in European Union countries, and that’s terrific, but let’s not drop the ball.

Should this entire process of distrusting country’s EU and NATO path, be rather a sign of Georgia’s ethnic minority communities showing mistrust, or distrust towards the Georgian state itself, or towards ethnic Georgian community itself, or towards the Georgian authorities, rather than, let’s say, interpreting all of this as Javakheti’s Armenian community showing signs of distrust towards Turkey as a NATO member? This would be perhaps a bit radical way to put it, but could we see such different opinions about Georgia’s foreign policy among ethnic minority communities as a sign of incomplete or failed national integration project?

On that latter point, perhaps to some degree. It is evident that they are in many ways not integrated. Living in a country and never having heard the name of the prime minister of that country… Not having access to information, not speaking the national language of the country, this is alienating. And [that is] a challenge. I am not suggesting Azerbaijanis be forced to speak Georgian, not at all. But there does seem to be alienation that could be contributing to that “I am not on board with this country’s foreign policy if I do not feel part of this country,” or if you feel, maybe, [you feel more] connected to another country.

NDI Poll of April 2019.

As to the first part of your question, interestingly, minority settlements are much more likely than the general population to support and approve of Georgian institutions and positively assess Georgian leaders and government bodies. So, I am not sure if the foreign policy views are a way, as you ask, of expressing dissatisfaction with the government in general, as they tend to be satisfied with the government. I think perhaps it goes back to having a different view of relations with Russia, as described above.

You have mentioned that Armenian community has strong views and are well-informed, unlike Azerbaijani settlements where people tend to “not know” or “refuse to answer”. How would you explain such differences? This is even paradoxical in a way. Javakheti region is more distant from Tbilisi, sometimes with no road connection to the capital city in winter, while Azerbaijani community lives just around corner from Tbilisi.

I am not sure, but perhaps there are cultural aspects to it, language aspects to it, maybe religion is playing a role in some way. In Azerbaijani communities in particular we have noted that women have considerably less information than the overall population. And that could be due to other cultural or traditional patterns in those communities… Perhaps Armenians [from Javakheti] are more connected to Yerevan, maybe their information sources are better. It is unclear to me. It is worth exploring, and figuring out what could be happening on the education front, for example.

What do you think, these diverging opinions about NATO and EU membership among different ethnic communities in Georgia hold for the future of Georgia? Imagine a scenario that tomorrow Georgia is entering NATO and the EU? What should one expect if ethnic minority communities remain alienated?

It could be hard for those communities. For the EU, they are largely supportive, but for NATO… That’s why we should not wait until that point happens and right now we need to be reaching out to these communities and explaining the benefits and providing accurate information about what NATO membership means and what it does not. There are misunderstandings about NATO’s role, there are beliefs that it is hurting religion, as I said, there are beliefs that it will lead to an occupation by American or Turkish forces in the country. Let’s reduce those elevated fear levels. Of course, it is not only a challenge for minority communities, as the majority of Georgians who support NATO integration at the same time believe joining NATO will cause Russian aggression. So for the broader population we need to address the fear of Russian aggression and preempt that concern about membership. Hopefully, one day, Georgia will be a NATO member, but before we get there, let’s make sure everyone is comfortable with the idea. They don’t have to love it, they don’t have to even approve membership, but they should not be afraid and should not believe false things. Let’s try to fix that first.