Insight | Abkhazia’s Energy Woes

As if the economic and social problems linked to the pandemic were not serious enough, Abkhazia finds itself amidst a severe energy crisis. The region fails in curbing crypto-mining, overcoming the Enguri HPP shutdown, and effectively managing the Russian electricity received as a temporary alternative source.

Power outages in the region are frequent and they have gotten worse with the beginning of winter. Uncontrolled cryptocurrency mining is frequently blamed as the central obstacle, but that problem masks deeper problems in relations with Tbilisi and Moscow.

The cornered Abkhaz authorities under new administration of Aslan Bzhania have to act expeditiously and resolutely to prevent the total blackout of the region and the growing social dissatisfaction with the existing situation.

Slump in Supply

The electricity problem in Abkhazia is old and deeply rooted. The region fully relies on free power from the jointly operated Enguri HPP, shared by Abkhazia and the rest of Georgia.

Roughly half of Enguri HPP generated energy goes to Abkhazia, but on January 20, the power plant stopped for scheduled reconstruction and went offline for approximately three months. Abkhazia lost its main source of cheap electricity.

Eventually, the power shortage crisis worsened to the extent that the Abkhaz authorities were forced to introduce the rolling power cuts to avoid a total shutdown of the system.

Chernomorenergo yesterday announced additional restrictions while stating that all its services are switched to the emergency work mode due to worsening weather and surged loads on the power grids.

Bzhania’s administration resorted to extreme measures, threatening district heads with dismissal unless they ensured a decrease of power consumption in their areas. Head of Ochamchire District Stanislav Amichba was dismissed from his post shortly after the warning, supposedly becoming the first victim of Bzhania’s new punitive policy.

Mining oneself dry

The surge of cryptocurrency mining in Abkhazia started in 2016 and gradually stretched the power grid to a critical point. The cryptocurrency miners were attracted by low real estate costs, the absence of cryptocurrency regulations, and an exceptionally low electricity tariff – since most of the electricity that Abkhazia consumes through Enguri HPP was essentially subsidized by Tbilisi.

For two years, the crypto-Eldorado thrived, but the toll it took on electricity consumption forced the authorities to take measures. It was too little, too late.

In 2018, Raul Khajimba’s administration imposed restrictions on the industry. Technically, this made mining illegal, but in practice, since the import of the relevant equipment was allowed, it had no effect. Bzhania’s administration inherited the problem, which continued to get worse.

Sokhumi changed its tack – authorities tried to regulate cryptocurrency business by restricting the import of mining computers, and introducing crypto-mining permits, increased electricity tariffs, and slapped the “miners” with new taxes.

In less than three months, the enforcement stalled. Money was not flowing into the coffers. In December 2020, cryptocurrency mining and the import of the relevant devices were, again, prohibited.

Shortly afterward Alkhas Gagulia, press-secretary of the local energy distributor, Chernomorenergo, stated that they managed to shut many crypto-mining farms, but the problem remained “grave.” Gagulia blamed “underground miners” for aggravating the situation, while also admitting that almost all electricity distribution substations in the region were overloaded.

Other factors

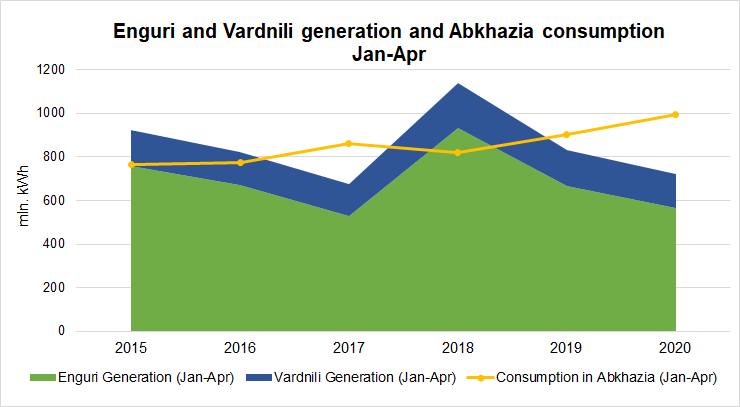

According to the informal agreement between Tbilisi and Sokhumi reached in 1997, the occupied region receives 40 percent of the electricity generated by the Enguri HPP, however, Abkhazia’s consumption in recent years has substantially exceeded the agreed quotas.

The region consumes more than it can afford. Yet, the solution to the issue is far from being simple. As Levan Mebonia, chairman of Enguri HPP Board points out – while Tbilisi has diverse sources for getting electricity, Abkhazia “has no other sources to turn to.”

As Abkhazia does not have natural gas, people use electricity to heat in winter, just when the water in the Enguri dam drops. Even before the crypto-mining took its toll, this created a chronic power deficit.

The power infrastructure in the region is outdated and in constant need of repair. Overloads on the substations mean that even when there is electricity to consume, regular power interruptions leave the population without electricity for indefinite periods.

Moreover, the power management and payment problem are further deepened with the nonfunctional electric meter system that impedes the relevant agencies to count and collect the cost of the consumed electricity.

Aslan Bzhania claimed that “complete restoration” of the region’s power system may cost about 10 billion Russian Roubles (USD 137 million) – the money that Abkhazia simply does not have.

But even with the complete restoration of the system, the issues of overconsumption will not fade away. President Putin promised Bzhania at their last meeting in Sochi that Russia would consider assisting the region in a costly gasification project, but it is unclear when this promise would materialize and whether locals will be able to pay for Russian gas.

Tbilisi’s position

Abkhazia consumes ten to fifteen percent more energy supplied by the Enguri dam than they are entitled to, Mebonia says. He worries, that with the mining trend continuing unabated, this share might increase further, undermining the entire Georgian energy security.

OECD’s International Energy Agency (IEA) has already marked the emergence of cryptocurrency miners as one of the substantial threats to the country’s power system stability.

Tbilisi might not be willing to provide electricity for free indefinitely – the original humanitarian gesture of goodwill is harder to defend when the electricity is apparently not used to warm homes, but to line the pockets of the cryptocurrency miners.

According to the Institute for Development of Freedom of Information (IDFI), Abkhazia’s growing energy use accounted for 93% of the Enguri HPP generation in 2020, while per capita consumption was 3.3 times higher than in the rest of Georgia. 2020 also marked the highest electricity consumption in Abkhazia (2.5 TWh), which is a 24% increase compared to the previous year.

So far, the major part of the Georgian political elite seems willing to continue supplying Abkhazia with electricity, as a gesture of goodwill, but also to mark the linkage with its occupied territory and its residents. But another stream of thought is gaining ground, which says Abkhazia should pay, or be cut from the power supply.

According to Levan Mebonia, supplying Abkhazia for free currently costs Enguri HPP GEL 30 million (USD 9 million) in monetary losses. With electricity rates growing all over Georgia, the discontent over the unbalanced distribution of the Enguri HPP power supplies might spread further among Georgians.

What’s Next?

With the inability to resolve the electricity crisis, Abkhazia faces multifold socio-political problems. The region’s fragile energy security is easily affected by turbulent circumstances, increasing the possibility of a full collapse of the system.

The ongoing situation demonstrates that the region cannot ensure even the recently introduced rolling power cuts, as it requires non-existent stability of the energy system and more supplies of electricity than Abkhazia can presently afford. Thus, should the critical situation persist, while the Abkhaz authorities further fail in implementing extreme measures promptly, the region risks staying without electricity.

The current energy crisis and possible worsening of the situation by the complete blackout of Abkhazia will most likely trigger another wave of public protests in the region. The last one, albeit not related to energy, ended with the ousting former leader of Raul Khajimba, while new leader Aslan Bzhania promised people to deal with the socio-economic problems, including energy issues.

Abkhazia is in need of urgent external financial and logistical assistance, but Sokhumi does not seem to address Tbilisi at this moment. Tbilisi, in its turn, might revisit its energy policy towards the occupied region and appeal to update the unfavorable for Tbilisi agreement with Sokhumi.

Russia helped Abkhazia to fill the power deficit created by the Enguri HPP construction works, but Sokhumi fails to fulfill the obligations in this regard as well. Kristina Ozgan, the region’s “economy minister” said Abkhazia owes Russia RUB 619 million (USD 8.3 million) for the February-April 2020 electricity supply. The full amount of the debt for the entire electricity supply is unknown.

Whether the region will be able to handle the financial commitments is thus another question. With the enhanced Russian assistance, the region’s reliance on Moscow further extends. The unresolved energy crisis puts Sokhumi under the risk to be fully dependent on Russia, while irreversibly yielding all the internal political and economic leverages.